There's a massive section of Northern Nevada that the Environmental Protection Agency considers potentially contaminated with high levels of mercury.

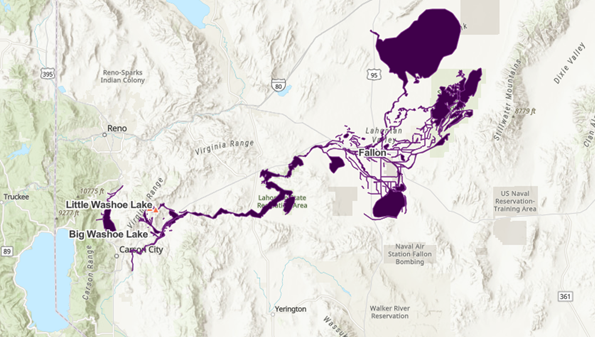

The heavy metal is in the water, plants, and animals within a 330-square-mile area east from Carson City, all the way through Fallon, to the Stillwater Wildlife Refuge.

In this 2 News Investigates piece in April, we looked into how dangerous the water and fish are for those who live and recreate there. But the mercury problem isn't just in the water; it's also in the soil. And that's becoming a bigger issue as developers look for new places to build housing.

While the mercury in the water-- which translates to high levels of mercury in fish, plants, and water fowl-- is the main concern, EPA officials are also keeping a close eye on the soil. In early May, a team of researchers spent a week sampling soil in the Six Mile Canyon area near Dayton.

"Here we are looking for metals," EPA Remedial Project Manager Sarah Watson explained. "We are looking for primarily mercury, arsenic, and lead."

Metals like mercury are an unpredictable danger, and in this case, one that's been moving and expanding its territory for more than 160 years. The area they're testing is just a tiny slice of a 330-square-mile chunk of Northern Nevada classified in 1990 as a "Superfund" site: a designation for the most polluted parts of the country.

The mercury comes from old mill sites that operated during the heyday of the Comstock Lode. Mills, which crushed and processed the ore from the mines, used mercury to extract the silver and gold. Mercury was the main method of extraction from about 1860 to about 1890. Some of that mercury was reclaimed, but the EPA estimates about 14 million pounds of it ended up washing downhill from 236 different mills into the Carson River watershed and the surrounding land.

"In this part of the site, we look near the mill sites, and kind of the drainages, you know where water goes over time," Watson said. "Floodplains, drainages, anything like that-- that's where we are looking for mercury."

Finding all the high concentrations of mercury, though, is a needle in a haystack problem. There's only so many soil samples they can take, and getting lab results is a slow process. So, during this site visit, they're using funding they've received through the recent infrastructure bill to test new technologies that could make the search way more efficient.

"I'm measuring soil reflectance with a backpack spectrometer," one EPA scientist on the team explained, showing an instrument that looks like a handheld metal detector, connected digitally to a monitor on his smartphone. "There's a lot of minerals in here that we can measure or detect using this instrument."

"We are able to see in real time all of these metals, and then we record the data for later," Watson said.

If these scanning technologies show results that match the physical soil samples, then they can use them to scan much larger areas, and let people know if they find high levels of mercury on their properties. If the mercury contamination is severe enough, the EPA will pay to take care of it, which they haven't been able to do on a large scale before.

"Usually the path we go is taking off the top two feet of soil and covering it with new, clean soil," Watson said. "Or sometimes just capping the soil: putting new soil on top of it."

Some landowners in the Fallon and Dayton areas have already gone through this process, and as Northern Nevada's housing crunch continues, more developers are eyeing open land like this, inching ever closer to the Superfund site boundaries.

"Lots of homes and economic development in the area," Watson said. "So there are houses being built along the highway, and it might end up in this direction."

This type of mercury is mostly dangerous if it's ingested. So eating the fish, water fowl, or water plants from the Carson River watershed is the biggest concern for the EPA. Mercury in the soil isn't likely to harm you unless you eat it. And that's not considered a major risk for most people. However, it is considered a risk for kids who may live on a contaminated site. If they play in the dirt and it gets in their mouths, over time that can cause major neurological problems.

There are a lot of families who have homes in the contaminated area and may not know it. And since the site wasn't even designated until 1990, any homes built before then could be on risky property.

Any homeowners who think they might live on Superfund land can check their address at this link. If their home is on the site, they can ask for a site visit, so crews can test the soil for mercury. If they find high levels of it, the EPA will pay for the mitigation. They say thanks to funding from the federal infrastructure bill, they can do more of these more quickly.